Elaine de Kooning continues to emerge from the shadow of her teacher and husband, Willem de Kooning, as an important artist in her own right. Thanks in part to major new scholarship by the National Portrait Gallery’s Chief Curator Brandon Fortune with their exhibition and book Elaine de Kooning: Portraits, as well as Cathy Curtis’s biography, A Generous Vision: The Creative Life of Elaine de Kooning, Oxford University Press 2017, and Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art, that Elaine’s important artistic legacy has begun to receive the market recognition it deserves.

The 1950’s were an artistically prosperous time for Elaine. She secured several solo exhibitions at notable galleries such as the Stable Gallery and the Graham Gallery and also participated in numerous noteworthy shows including the Ninth Street Show, 1951, Young American Painters at the MOMA, 1956, and Artists of the NY School: 2nd Generation at the Jewish Museum, 1957. She was included in the Ten Best list in ARTnews Magazine in 1956 as well as the Great Expectations I article written by Thomas Hess that same year. At the root of great abstraction, there is usually great conflict. The “frenzied rush” embodied in her canvases of the 50’s and early 60’s is in fact part of a sustained level of engagement with an adversary…the adversary being herself.” *

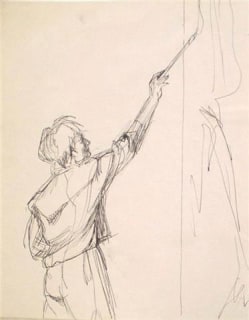

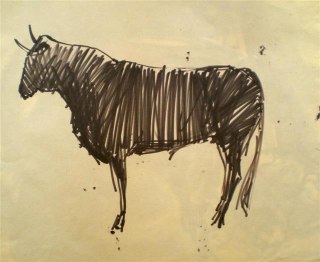

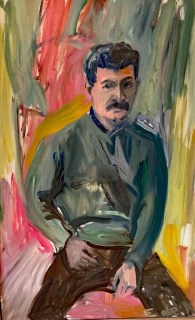

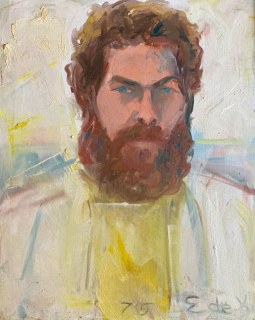

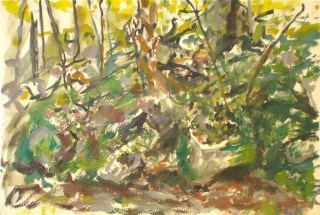

Elaine would continue painting in an abstract manner for the rest of her life, informing her portraits, landscapes, Bull series, Sports series, Bacchus series and Cave series. Each of her series spanned a finite portion of her career, while portraiture always was threaded into her creative output spanning her entire 45 year career. Most notable is her commission to paint a series of portraits of President John F. Kennedy, including one for the Truman Library in 1963, just before Kennedy’s untimely death. Her mastery in this genre is exemplified in her ability to effectively convey the moment, a feeling, a gesture, a sense of likeness about the person as opposed to their physicality. She wavered between precisely configured portraits and those of extreme abstraction, many times with faceless sitters in the early to mid1950’s. But regardless of the approach, the character of Elaine’s subjects was always alive with a personality and gesture unique to sitter. The National Portrait Gallery’s Elaine de Kooning: Portraits exhibition in 2015-16 drew over 200,000 visitors. Levis Fine Art worked closely with the team at the National Portrait Gallery to gather additional scholarship and to assemble many of the paintings for loan to the museum.

In her series paintings, Elaine brought the same level of likeness as her portraits, with an added immediacy to the moment. Her brushstrokes dance around the figures, sweeping up and around, in and out, constantly shaping the multi-dimensional contours of their actions, creating a transcendence of energy throughout the entire painting; evidence of her extraordinary talent as an “Action” painter.

* Helen Harrison, Elaine de Kooning, the Early Years, This essay was included in the 1992 Memorial Exhibition catalog, Elaine de Kooning by Jane K. Bledsoe, with essays by Lawrence Campbell, Helen A. Harrison and Rose Slivka.

© 2019 Levis Fine Art, Inc.